I’m always a bit confounded by stories of time travel, easily lost in the logical fallacies and conundrums. But when you strip the mechanics away and just enter into a state of suspended disbelief that it might be possible, time travel stories are remarkably profound. To have a character with full knowledge of the present time be able to walk around and marvel at a prior time uncovers interesting juxtapositions, exposes similarities and differences, and allows you to evaluate your own time period afresh.

I just finished Time and Again by Jack Finney, which offers a time travel vehicle that allows his character to step back into a time before many of our modern problems—world wars, pollution, climate change—and enjoy a less jaundiced perspective. More important, though, the time travel opens his eyes to the humanity and complexity of the people, long dead now, walking around living and breathing in that present:

“In some ways, the sight of that ordinary man whom I never saw again is the most intensely felt experience of my life. There he sat, staring absently out the window, in an odd high-crowned black derby hat, a worn black short-length overcoat, his green-and-white striped shirt collarless and fastened at the neck with a brass stud; a man of about sixty, clean-shaven.

I know it sounds absurd, but the color of the man’s face, just across the tiny aisle, was fascinating: this was no motionless brown-and-white face in an ancient photograph. As I watched, the pink tongue touched the chapped lips, the eyes blinked, and just beyond him the background of brick and stone house slid past. I can see it yet, the face against the slow-moving background, and hear the unending hard rattle of the iron-tires wheels on packed snow and bare cobbles. It was the kind of face I’d studied in the old sepia photographs, but his hair, under the curling hat brim, was black streaked with gray; his eyes were sharp blue; his ears, nose, and freshly shaved chin were red from the winter chill; his lined forehead pale white. There was nothing remarkable about him; he looked tired, looked sad, looked bored. But he was alive and seemed healthy enough, still full-strength and vigorous, perhaps with years yet to live-and I turned to Kate, my mouth nearly touching her ear, to murmur, ‘When he was a boy, Andrew Jackson was president. He can remember a United States that was -Jesus- still mostly unexplored wilderness.’ There he sat, a living breathing man with those memories in his head, and I sat staring at the slight rising and falling of his chest in wonder.”

The premise for time travel in this book, for what it’s worth, is that the times are all existing at once, in the way a river exists even though, when you’re in it, you can’t see up past the bends ahead, or back to the parts you’ve already traveled. You merely step into a prior time period once you strip from your mind all the things tethering you to the present. Or, using a different metaphor, time is like transparencies in a book, each laid over the same foundational picture, but each distinct as well. You simply turn to the right page and step in.

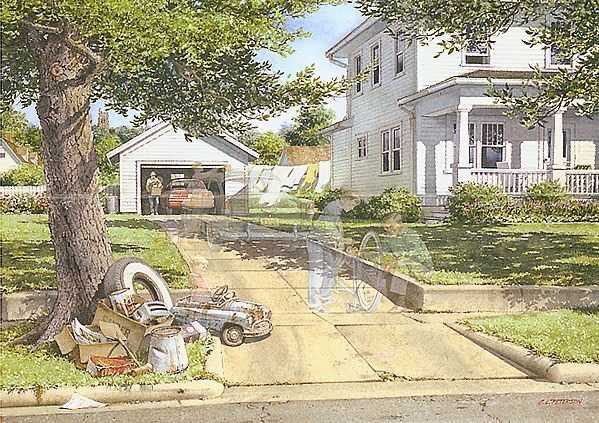

The transparency metaphor reminds me of the art of Charles Peterson, the opaque areas reflect action of the present, but the wisps reflect prior generation that lived their lives fully in that spot in the past.

In many ways, we are time travel machines in our own right. We can look at history and reflect how we might have behaved in the same time and place had we those choices and circumstance. We can step out of our own present day group think now and consider how things may hold up with a longer view from the future looking back.

What is happening right now in front of us, that future generations might look back on fondly, or with horror? How can we bring those insights to bear to inform how we act right now?