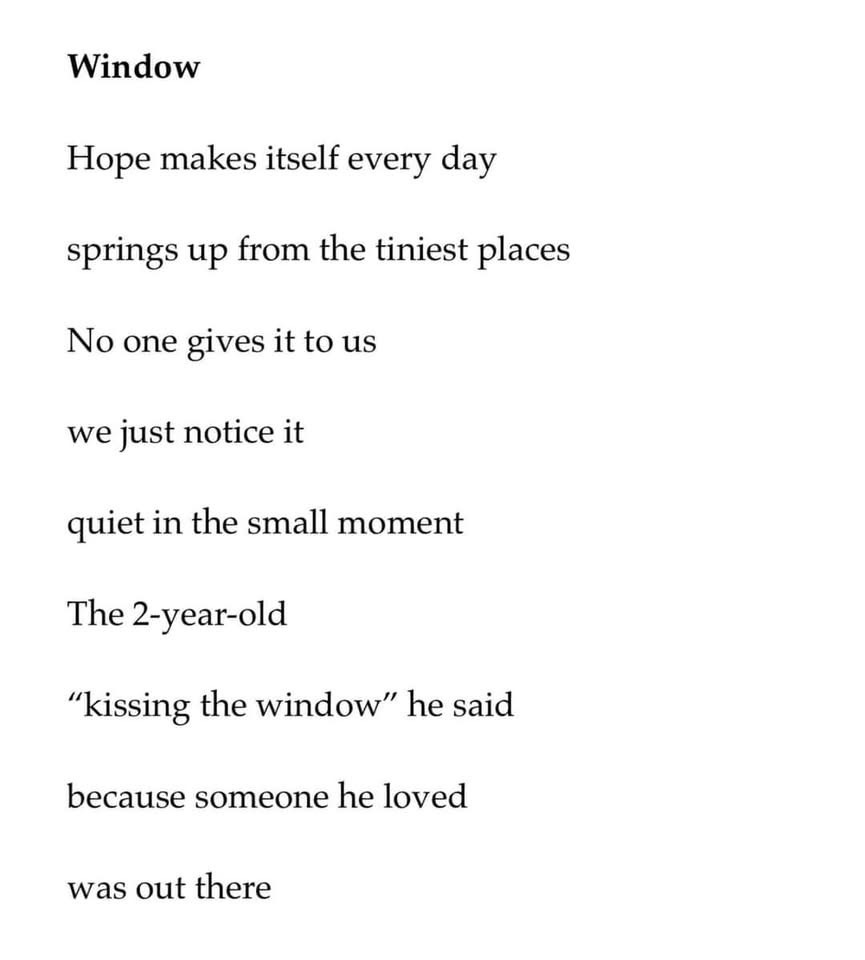

Hope in the tiniest places.

Today, notice signs of hope in unlikely places. In the smile of a baby, the fledgling arguments for peace by a child, the chink in the armor of an opponent.

Today, notice signs of hope in unlikely places. In the smile of a baby, the fledgling arguments for peace by a child, the chink in the armor of an opponent.

I was recently reminded about a story from 2017 where two little boys were caught in a rip tide and swept out to sea. Their entire family and four woud-be rescuers tried to swim out to save them but ended up similarly stranded. Officials on shore stood, helpless, waiting for a rescue boat while the family and would-be rescuers floundered.

But then the people on the beach did a remarkable thing. People from all walks of life, across every possible difference or division, linked arms together and formed a human chain stretching out into the ocean until they reached those stuck and and then passed them person to person, beginning with the little boys, Noah (11) and Stephen (8), and ending with their grandmother who had tried to save them, back to safety.

Stories like this don’t get a lot of press. But it’s why we’re here.

To help each other. To make a difference.

What makes some people able to empathize more than others, able to help in dire circumstances, able to put the greater good above the personal good? Bryan Stephenson, founder of the Equal Justice Institute, fierce advocate against systemic racism, and criminal defense attorney for those on death row explains: “I do it because I’m broken, too.” That recognition of a common humanity and brokenness by a system that needs changing propels him to fight.

Who among us isn’t broken? Because we all are bound together, we all suffer in an unjust world. Because we all have known pain, we all have the capacity to put ourselves into the shoes of those hurting.

In his book, Just Mercy, Stephenson explains:

My years of struggling against inequality, abusive power, poverty, oppression, and injustice had finally revealed something to me about myself. Being close to suffering, death, executions and cruel punishments didn’t just illuminate the brokenness of others; in a moment of anguish and heartbreak, it also exposed my own brokenness. You can’t effectively fight abusive power, poverty, inequality, illness, oppression, or injustice and not be broken by it.

We are all broken by something. We have all hurt someone and have been hurt. We all share the condition of brokenness even if our brokenness is not equivalent. I desperately wanted mercy for Jimmy Dill and would have done anything to create justice for him, but I couldn’t pretend that his struggle was disconnected from my own. The ways in which I have been hurt–and have hurt others–are different from the ways Jimmy Dill suffered and caused suffering. But our shared brokenness connected us.

Paul Farmer, the renowned physician who has spent his life trying to cure the world’s sickest and poorest people, once quoted me something that the writer Thomas Merton said: ‘We are bodies of broken bones.’ I guess I’d always known but never fully considered that being broken is what makes us human. We all have our reasons. Sometimes we’re fractured by the choices we make; sometimes we’re shattered by things we would never have chosen. But our brokenness is also the source of our common humanity, the basis for our shared search for comfort, meaning, and healing. Our shared vulnerability and imperfection nurtures and sustains our capacity for compassion.

We all have a choice. We can embrace our humanness, which means embracing our broken natures and the compassion that remains our best hope for healing. Or we can deny our brokenness, forswear compassion, and, as a result, deny our humanity

…So many of us have become afraid and angry. We’ve become so fearful and vengeful that we’ve thrown away children, discarded the disabled, and sanctioned the imprisonment of the sick and the weak–not because they are a threat to public safety or beyond rehabilitation but because we think it makes us seem tough, less broken. …We’ve submitted to the harsh instinct to crush those among us whose brokenness is most visible. But simply punishing the broken–walking away from them or hiding them from sight–only ensures that they remain broken and we do, too. There is no wholeness outside of our reciprocal humanity.Just Mercy, by Bryan Stephenson

How many of the problems we face today can be mitigated by recognizing our common humanity, by following the Golden Rule of treating others how we would have them treat us, a tenet found in many of the world’s religions? How would we have others treat us if we were the elderly, the sick, the refugee, the hurt, the accused, the other? Each of us would benefit from considering things from this perspective. Bryan Stephenson continues:

Whenever things got really bad, and they were questioning the value of their lives, I would remind them that each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done. I told them that if someone tells a lie, that person is not just a liar. If you take something that doesn’t belong to you, you are not just a thief. Even if you kill someone, you’re not just a killer. I told myself that evening what I had been telling my clients for years. I am more than broken. In fact, there is a strength, a power even, in understanding brokenness, because embracing our brokenness creates a need and desire for mercy, and perhaps a corresponding need to show mercy. When you experience mercy, you learn things that are hard to learn otherwise. You see things you can’t otherwise see; you hear things you can’t otherwise hear. You begin to recognize the humanity that resides in each of us.

…I began thinking about what would happen if we all just acknowledged our brokenness, If we owned up to our weaknesses, our deficits, our biases, our fears. Maybe if we did, we wouldn’t want to kill the broken among us who have killed others. Maybe we would look harder for solutions to caring for the disabled, the abused, the neglected, and the traumatized.Just Mercy, by Bryan Stephenson

We are all broken. Some of us don’t acknowledge that. We have all hurt and been hurt. It is that humbling insight that can help us recognize our common humanity across all divides. If we just have the eyes to see and the ears to hear. Stephenson refers to an unnamed pastor who would preface singing: “The minister would stand, spread his arms wide, and say, “Make me to hear joy and gladness, that the bones which thou hast broken may rejoice.”

Amen to that.

Nowhere can you experience life from someone else’s point of view better than in a book. You can feel what it is like to be another gender, race, lifeform. Time is no limitation–you might experience life now, in the past, in the future. Opening those pages allows you to step inside someone else’s shoes. And that can’t help but change you, stretch your empathy, and expand your experience.

What would it be like if you could talk over things with those characters? Ask them about life in their shoes?

In a very cool project, doing exactly that, library patrons have the chance to check out a human book. Hopefully the human book they check out will be someone with a different life experience and perspective.

So check out a book, or maybe talk with someone as unlike from you as you can find. You’ll be surprised at all the things you have in common.

When you have the power, or are on top, or when everything is going your way, it’s only natural to want to strut. You don’t want to think about a time when you might be powerless, on the bottom, or have the world against you.

That’s a downer, isn’t it?

But that’s exactly where religion urges us to go, to think about the world from other perspectives, to consider what life is like for people without your privilege, to have empathy with the unfortunate. Because, after all, if you were in their shoes, wouldn’t you hope they would look out for you?

Bless the comforters, those who reach out and see others hurting and grief stricken, and offer them solace. Who sit with those going through difficult times, and give of their presence. Who offer kind, comforting words.

We sometimes think those who are good at comforting don’t know loss of their own, but the opposite is probably true.

As said by Rainer Maria Rilke:

Do not assume that he who seeks to comfort you now lives untroubled among the simple and quiet words that sometimes do you good. His life may also have much sadness and difficulty, that remains far beyond yours. Were it otherwise, he would never have been able to find such words.

Perhaps the only good to come of great loss is the ability to recognize it in others and offer them comfort and companionship.

Bless the comforters.

Nothing is more important than empathy

for another human being’s suffering.

Not a career.

Not wealth.

Not intelligence.

Certainly not status.

We have to feel for one another

if we’re going to survive

with dignity.~Audrey Hepburn

Studies show empathy, the ability to put yourself in another person’s shoes and consider their point of view, might be on the decline in the United States. With a lack of empathy comes the possibility of othering, cruelty, and self-absorption.

What can we do to increase our empathy for others?

Consider this novel idea: empathy walks. Literally mirroring someone’s walk, not in a stalkery or critical way, but as a silent practice in visualizing what it must be like to be that person. Consider this example:

It all started on one of my regular walks into town. I was head-down, in a hurry, when I noticed an older woman ahead of me. She was walking slowly—agonizingly slowly, if I’m being honest—and my first instinct was annoyance. But then I thought about the old acting school exercise. What if, instead of speeding up to dodge her, I matched her pace? So, I slowed down, mimicking her small, deliberate steps, the way she slightly leaned to one side, her arms swaying as if carrying invisible weights.

And then it hit me: empathy. Not the mushy, Hallmark-card kind, but a physical understanding of what it might feel like to be her. As I moved like her, my irritation evaporated. I didn’t just see her; I felt her. I thought about the phrase “walk a mile in someone else’s shoes,” and realized it’s not the shoes that matter; it’s the walk….

So, the next time you’re out walking, try it. Pick someone ahead of you and mimic their stride. Notice where they’re tight, where they’re loose, how they carry themselves. Let their tension teach you about your own. Let their walk reshape yours. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll feel a little less separate and a little more connected—to them, to yourself, and to this messy, beautiful, shared experience we call being human.

We are all different, with different joys and burdens, challenges and delights. We each bring a different package of strengths and weaknesses to any situation. As we begin to appreciate the different points of views and perspectives of those around us, our empathy grows, and with that, our own world expands.

Are these the times that try people’s souls? What does it mean to have your soul tried anyway?

I’ve been thinking about this picture:

Those faces, contorted in rage, caught for history. This picture, reflecting a military presence during school desegregation, anticipating, presumably, a violent reaction from the mob, freezes a moment in history. I wonder how those women feel looking back on it. Would they be ashamed to have been part of a mob hurling epithets at this young woman? Would they feel contrition?

That period in history was certainly turbulent. Fraught with animosity directed at those seeking an education, because of the color of their skins, the women in the crowd wear their anger and hate openly in their faces.

We too are in turbulent times. Whole industries are churning out content intended to divide us, to make us hate others like the women in this picture? We are fed misinformation and disinformation designed to further these divides. Presumably the motive for this hate industry is profit, but at what expense? Will this hate-filled rhetoric cost souls?

It will certainly try them, and it is our job to protect our souls. To listen deep to the wisdom that seeks love and peace, harmony and cooperation. To deplug from the constant rhetoric of othering and hate.

It’s a loud angry world. Hush and listen to the harmony of your soul.

One of my personal heroes, Jimmy Carter, 100 years old, has passed away, and the world is a bit darker without his light. He has been such a wonderful example of walking the walk. He said:

“My faith demands – this is not optional – my faith demands that I do whatever I can, wherever I can, whenever I can, for as long as I can with whatever I have to try to make a difference.”

What a wonderful way to look at our possible impact. Using what we have, not waiting until we have more or better resources or to be older and wiser, or wishing we were younger and stronger. Right now, with what’s available.

And wherever we find ourselves, adopting a bloom where you’re planted attitude. Even if we are in our own harsh spot. Considering what can we do here.

And always looking for opportunities to do good. Not necessarily solving the world’s problems, but doing your own little bit of good. Right here, right now.

Let’s go.

Thank you, President Carter, for this reminder. You will be missed.

How do we make sure we aren’t just staying alive but staying vibrant? Making our moments count? Making an impact and difference in the lives of those we care about? Making our lives matter?

Consider Virginia Woolf’s words:

Whatever happens, stay alive. Don’t die before you’re dead. Don’t lose yourself, don’t lose hope, don’t lose direction.

Stay alive, with yourself, with every cell of your body, with every fiber of your skin.

Stay alive, learn, study, think, read, build, invent, create, speak, write, dream, design.

Stay alive, stay alive inside you, stay alive also, outside, fill yourself with colors of the world, fill yourself with hope, with Wow Scenery.

Stay alive with joy.

There is only one thing you should not waste in life, and that’s life itself.

How do we become hard-hearted as we age, focused so much on ourselves and our own needs? How do we deaden ourselves to community and lives being lived around us, turning inward and reclusive, dying really to the fabric of life?

I just watched the muppet version of Christmas Carol which did a great job of capturing Charles Dickens’s classic story about the transformation of Ebenezer Scrooge, first his turning in, the selfishness, the greed, the callousness to those around him, his miserliness in spirit and deed.

But then, with the spirits’ intervention, Scrooge has an epiphany and realization that life is a looking out, a contributing, a generosity and an overflowing of joy. His life becomes filled with vibrancy and exuberance and a realization of the difference he can make in the here and now. At that moment, he becomes part of something larger than himself, alive with possibility and connection.

Each of us faces Scrooge’s dilemma. We may not be miserable misers, but perhaps we have turned in to focus on ourselves. Perhaps we’ve become callous to the suffering around us and blind to the good we can do. Perhaps we’ve lost the joy.

Scrooge’s story reminds us all that it isn’t too late to turn over a new leaf, to reach out to those around us, to wear our love and concern on our sleeves, to care. And by spreading joy, we find ourselves drenched in it as well.