Connections in a big old world.

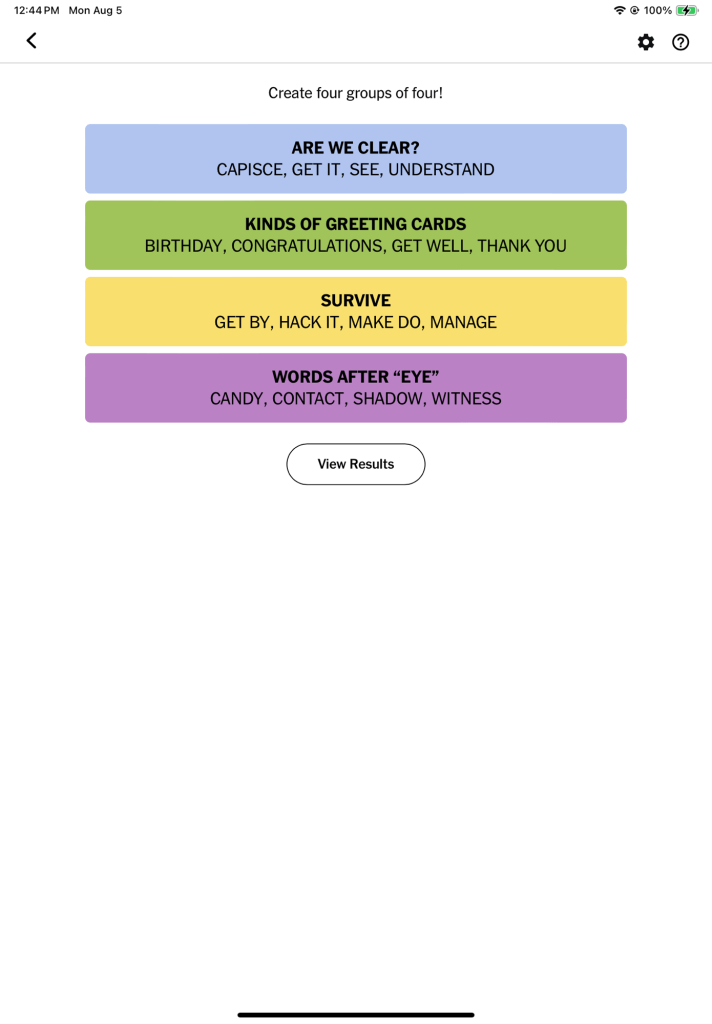

Every morning, I wake up and play games. My favorite these days is Connections, a collection of 16 words that you need to group in four groups of four based on a shared connection. Here’s the solution from one last week:

Now, looking at the solution, it’s easy to see the connections. Not so, though, when the words are all scrambled and the connections are unclear. Words may have more than one meaning or be multiple parts of speech. Often the answers are homonyms or are missing a letter. It can be challenging to find the connections among the words.

So, too, with the connections among people. There are some obvious superficial connections perhaps— gender, political affiliation, nationality, religion, age. But what of those deeper, hidden ones? How do we find those to help us feel more like a community?

I thought about this when reading an article about how an introvert, Jay Krasnow, made friends. He had struggled to find true connections at work functions or forced social gatherings, but when he dug deeper, to consider the things he was passionate about and find others who shared those passions, he found the connection he was looking for. He explains:

My failure at connecting wasn’t due to a lack of trying. I spent my 20′s and 30′s collecting and studying books on how to network, forge friendships and build character.

Yet, my principal achievement from reading these books was that I became adept at identifying when other people had read these same books. Meanwhile, my networking skills didn’t significantly improve. Even worse, I felt that by reading books with titles like “How to Talk to Anyone,” I was turning myself into a robot that spewed out inauthentic lines to people who I genuinely wanted to know.

There had to be a better way to build relationships.

For Jay, he decided to start a book club, not one reading the same book, but one where you came and told people about the book you were currently reading. It took off, people came. And those relationships centered on a shared passion spilled over into other friendships:

Connecting with other people through books seemed natural, but I didn’t know if anyone would come. I was prepared to read my book quietly if no one else showed up. Fortunately, both my friends came, and we were joined by one other person we didn’t know.

After the first event, more people started coming, and I started making new friends almost immediately.

The group’s membership grew exponentially. It wasn’t long before I was inviting my new friends to dinners and other events. Because we had established we shared a similar passion, it was easy to branch out from there and find other things to do and talk about.

I wonder if this is what the world needs right now— connections based on a shared love or passion. So much of identity seems tied into a shared hatred or shared anger over something. It seems like that just leads to more loneliness and separation.

Time to try a new approach.