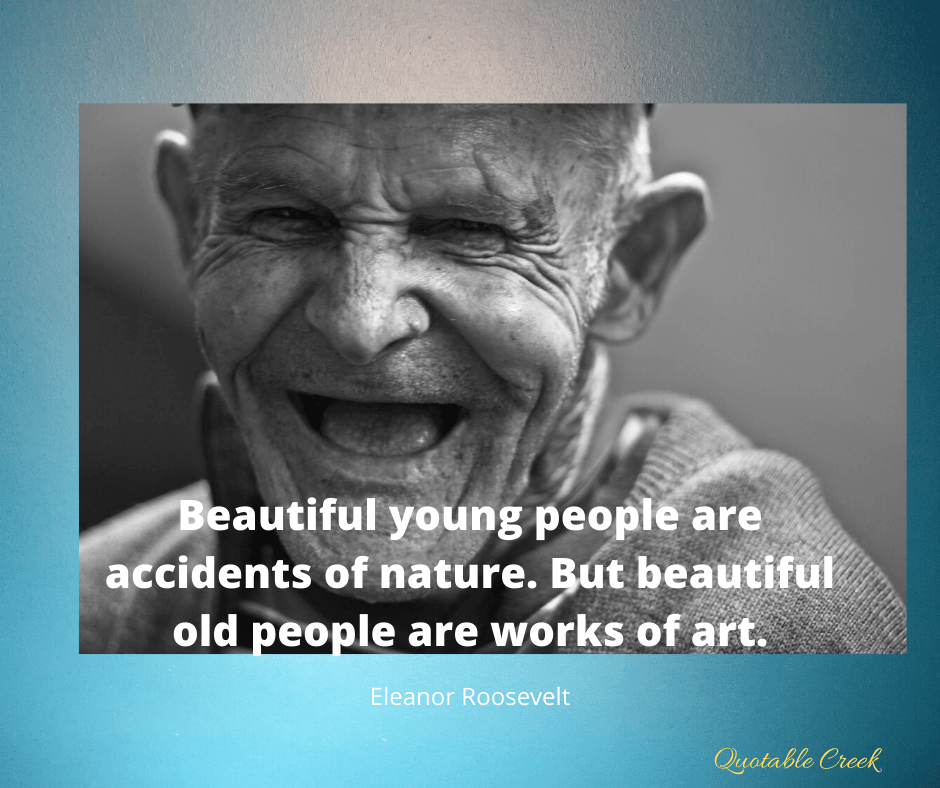

Aging, well, gracefully?

There is a certain tipping point where life becomes weighted with loss. Things shift from everything out ahead to having a full past. In many ways, it is challenging, sad, and frustrating. But in some, it can be liberating.

Consider these words from Anne Lamott:

“So many indignities are involved in aging, and yet so many graces, too. The perfectionism that had run me ragged and has kept me scared and wired my whole life has abated. The idea of perfectionism at 60 is comical when, like me, you’ve worn non-matching black flats out on stage. In my experience, most of us age away from brain and ambition toward heart and soul, and we bathe in relief that things are not worse. When I was younger, I was fixated on looking good and impressing people and being so big in the world. By 60, I didn’t care nearly as much what people thought of me, mostly.”

“I do live in my heart more, which is hard in its own ways, but the blessing is that the yammer in my head is quieter, the endless questioning: What am I supposed to be doing? Is this the right thing? What do you think of that? What does he think of that?”

“A lot of us thought when we were younger that we might want to stretch ourselves into other areas, master new realms. Now, I know better. I’m happy with the little nesty areas that are mine. For some reason, I love my softer, welcoming tummy. I laugh gently more often at darling confused me’s spaced-outed ness, although I’m often glad no one was around to witness my lapses.”

“It’s Good to Remember: We Are All on Borrowed Time,” by Anne Lamott.

I do ‘feel I live in my heart more’ as she notes. And that grief is keen and biting. Almost as if my mind is at war with itself, one half realizing that death is a natural part of life, inevitable. While the other half refuses to accept the new reality. And yet, ultimately, it is our impermanence that gives our lives luster and meaning. And acceptance, if it should come, may not bring comfort, but peace.